The 14 texts which follow, each reflecting the writer’s viewpoint, are so rich and comprehensive that it is impossible for an introduction to fully encompass their essence. In most cases, the beginning, middle and end of the text refers to the barbaric act committed by Elgin.

I have therefore chosen not to repeat those well-known, well-rehearsed and well-discussed issues. Instead, I chose to contribute certain new arguments to the cause of returning and reunifying the marbles or sculptures of the Parthenon in the Acropolis Museum, which is their newly designated place of protection and display, a place that stands in close dialogue with the very monument from which those severed members originally came.

As a rich body of international bibliography on the subject makes clear, it is now obvious to all that the so-called firman which Thomas Bruce, the Earl of Elgin and ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1799-1803, is supposed to have procured from the Supreme Porte, in other words from Sultan Selim III, does not exist. If such a document had existed, it would have been submitted to the examining committee of the British House of Commons in 1816 – and the whole question of legality, and restitution claims by the Greek state, would have taken a different turn.

According to Elgin’s testimony to the committee, the original document sent by the Turkish authorities to Athens was lost. The Reverend Philip Hunt, the ambassador’s assistant, offered in testimony what he could recollect, 14 years later, of a translation of a French version of the original firman into Italian and later rendered into English.

However:

ONE

Official firmans of the sultan were always made in two copies, of which one was kept in the official archives and the other was sent to the designated recipient. In the course ofall the investigations made hitherto, the original, archived version of the firman has never been found.

TWO

Genuine firmans were despatched through a special designated messenger or an authorized individual or delivered by captains of the Turkish navy. In this case the so-called firman was brought to Athens by Philip Hunt, Elgin’s assistant.

THREE

For the actions that Elgin was seeking to undertake on the Acropolis, formal permission was indeed necessary because according to an unwritten Ottoman law, marble in all its forms – works of art, ancient or otherwise, and the raw material itself – belonged to the sultan. All the more so if marbles were to be removed from such a well preserved surviving decoration of a monument that was well respected by Ottoman officials as a “temple of the idols” – namely the Parthenon.

Thanks to the authentic firmans that were issued over the years for various purposes, we can ascertain what a genuine sultan’s firman looked like, what formalities it observed, what turns of phrase and calligraphy were used, and all its other features. I will not enumerate the hundreds of examples that might be mentioned. I will focus instead on two sultan’s firmans which are of immediate relevance, because they concern two protagonists of our story – Lord Elgin and Lord Byron. They are also, of course, close chronologically. The first is dated 1802 and was brought to light by Dyfri Williams. It is the official passport-firman granted to Elgin which authorized his trip to Athens and the Aegean archipelago. The second was granted to Byron in 1810 and is presented here for the first time, thanks to the generosity of a particular individual. It is the official travel document which was issued to Byron: its interpretation and presentation are the work of Ilias Kolovos, a scholar of Ottoman history.

When one compares these two original passport-firmans, they turn out to be very much alike in format, despite the fact that Sultan Selim III died in 1808 and was replaced on the throne by Mustafa IV. If we then compare those two documents – the one issued to Elgin and the one granted to Byron, which is available to us in Turkish (in Roman script) as well as English translation – with the so-called firman granted to Elgin which supposedly allowed him to remove sculptures from the Parthenon – at least according to the Italian translation, and its later English rendering. It becomes clear – as was demonstrated by the Ottomanist scholar Vasilis Dimitriadis at a conference on the Parthenon and its sculptures – that Elgin’s so-called permit is anything but a genuine sultan’s firman. He would have needed to get the personal authorization of the sultan, instead of merely relying – as he did - on the deputy to the Grand Vizier, Sejid Abdullah. That deputy was standing in because the actual Grand Vizier – Kor Yusuf Ziyauddin Pasha, otherwise known as Djezzar, (the butcher) – was at the time in Egypt.

Given that the so-called permit for the removal of the sculptures was not a genuine sultan’s act, but merely a decision issued by the deputy to the Grand Vizier – assuming that the Italian translation is real and accurate –how can anyone justify the still-adamant denial by the British authorities and the British Museum that what took place was an act of vandalism – indeed, a plundering of sculptures that were integral to the monument, constituent parts of the Parthenon? Or justify their refusal to return and reunify the marbles in the Acropolis Museum?

To put it more bluntly, how is it that certain officials – in the British Museum and elsewhere in Britain – still regard as acceptable a flawed purchase in 1816, and an arbitrary decision by Parliament in 1963, insofar as these relate to the ongoing captivity of the Parthenon marbles?

This is not the place to delve deep into the reasons for that insistence. Let me focus instead on some initiatives aimed at resolving the issue, in accordance with the realities of the 21st century. In addition to the strong and respectable arguments laid out by many people over two centuries – especially by Melina Mercouri in 1982-83 – all the way up to 2021, a number of developments stand out.

ONE

In September 2021, UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property (ICPRCP) adopted a decision which clearly recognizes Greece’s aspirations as rational, justified and ethical. It also affirmed the intergovernmental nature of the dispute and called for consultations between Britain and Greece.

TWO

A particular methodology was followed in the return and reintegration of the so-called Fagan fragment from Palermo. This was the first return which was treated as a matter from State to State. Initially, in January 2022, the return was presented as an unspecified “deposit” – and then, in June 2022, came the permanent reintegration of the fragment into the Parthenon frieze: an act that was underpinned not merely by legal norms and technicalities but also by the friendship between two nations - Greece on one hand, Italy and in particular Sicily on the other – who share common values.

THREE

In March 2023, Pope Francis returned three fragments of the Parthenon, as an expression of universal truth, for the definitive reunification of the monument’s scattered sculptures.

The British government and the British Museum would do well to ponder the significance all these developments, while also considering certain other factors such as:

ONE

The consistent majority of British public opinion [in favour of return]

TWO

The continued support expressed by the near-entirety of the British press

THREE

International public opinion, which favours the reunification of this world-renowned monument…so that it can be properly presented in all its integrity as a work of supreme architectural and sculptural beauty; and experienced as a symbol of democracy by people of allgenerations and national origins.

And in case those arguments fail to persuade doubters of the moral soundness of Greece’s case, I will add yet another one.

Over the past few decades, there have been some well-known cases of restitution of art works – for example to Italy or to Africa. Such returns have even been made by Britain. Let me specify one example.

On August 1, 2008, the upper section of a funerary monument was returned to Greece from New York.

It was made of Pentelic marble and it dates from the late fifth century – about 410 BCE, shortly after the completion of the Parthenon. Μy Professor George Despinis, as early as 1993, had proven that the piece came from a funerary monument whose lower half had been discovered in the soil of Attica – in Porto Rafti – and was then conserved in the Museum of Βrauron in Attica.

After some negotiations, the purchasers of the upper part – who were American citizens –gave that segment back to Greece, while Greece acknowledged that the purchase had been made in good faith. The matter was settled and the two parts of the funerary monument are reunited in a Greek museum.

I will now refer to a rather similar case, concerning the Parthenon. The lower part of segment number XXVII of the Parthenon frieze – showing a charioteer, part of a chariot and a stable lad –is in the Parthenon Gallery, while the upper part is in the Duveen Gallery of the British Museum.

Just about anybody will readily understand the similarity of the two stories. In particular, the morally equivalent fate of the piece of marble that was broken off and plundered by Elgin’s team and the severed upper part of the funerary monument – while in both cases, the lower sections remained in the place where the works had been fashioned.

So given that the principle of repatriation was applied in the case of the artefact in New York, exactly the same norm should apply in the case of the broken segment from the northern side of the Parthenon frieze.

One could of course take the argument further and note that in the case of the funerary monument, the buyer was in legal terms an individual rather than a state; and then observe that under international law, no state can retroactively justify illegal acts by one of its citizens on foreign soil - given that in such cases international law supersedes anything enacted by local or national legislatures.

In view of all that, how can it be that a state, in this instance the British state, vindicates the vandalism and plunder perpetrated by one of its subjects? Considering that Elgin, as a private individual, committed an act of vandalism, along with his associates, and broke off sculptures from the Parthenon - only to transport them to England in order to decorate his home, where they would have stayed if he had not gone bankrupt.

People who persist in justifying the purchase of 1816 must surely accept this: the mostone might say is that this decision amounted to a “receipt of stolen goods” in good faith – as was the case with the purchase of upper part of the funerary monument from Brauron.

In no way can they justify the illegal actions of a British subject, Lord Elgin – in view of the considerations I have laid out.

Nor, by the same token, should any government οr state wish to carry the moral burden that results from such tainted acts. I believe the moment has come for our British friends to take a noble decision and rid themselves of the moral burden which Elgin - rashly, and in pursuit of personal gain – laid on Britain, the British Museum and the people of Britain.

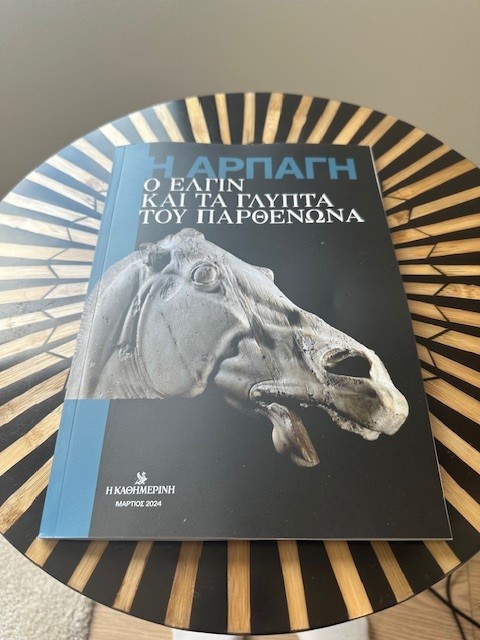

The above text was the lead article in a Kathimerini supplement published 17 March 2024, entitled:H AΡΠΑΓΗ, 'Tthe Grab, Elgin and the Parthenon Sculptures'

In the same supplement BCRPM member Bruce Clark's article 'Laws, democracy and hypocrisy' was also plublished.

Photo credit for the images of Professor Stampolidis: Paris Tavitian